|

| The coat of arms of San Gil, Colombia (1694) |

Interestingly enough, the most famous Rueda is also from Andalucía: early Spanish playwright Lope de Rueda (born c.1510 in Sevilla, Spain; died 1565 in Córdoba, Spain). As an older performer of rough, knockabout comedies, Lope de Rueda inspired a teenage Miguel de Cervantes, future author of "Don Quixote," to write his own plays.

The Spanish word Rueda, meaning "wheel," stems from the Proto-Indo-Europeans who traveled in carts pulled by oxen from the Eurasian steppes around 3000 BC and settled in Iberia by 2500 BC. Their reconstructed root word "hret," meaning to roll, evolved into the Latin word for wheel, "rota," which in turn transformed into similar words through Europe: "rueda" in Spanish, "roda" in Portuguese, Catalan and Galician, "roue" in French, "ruota" in Italian, and "errota" in Basque.

As early as 1535, Spaniards with the last name Rueda are recorded heading to "Nueva Granada" (now Colombia). "Rueda" appears in Sangre Judía by Pere Bonnin, a list of 3,500 surnames associated with Jews or converted Jews, as gleaned from Spanish Inquisition records and censuses of Jewish ghettoes. Sadly, at least two Colombian historians with the last name Rueda insisted in their writings that people from Santander, Colombia only had "Old Christian" blood, with one even saying they were not "dirtied" by Moorish or Jewish blood. Such attitudes were commonplace, racist, and false. However, it's also close to impossible to prove that Iberian ancestors of Latin Americans were "Jewish" or "Sephardic," given a dearth of documents and the historical risks that came with publicly admitting Jewish or Muslim roots. Spanish Inquisition cases represent a fraction of the population with Jewish ancestors. Many Latinos have trace percentages of "European Jewish" DNA in their admixture, representing collective ancestral amnesia, in the face of centuries of Iberian persecution.

THE FOUNDING RUEDA (AND LÓPEZ)

|

| The Rueda household in the 1620 census of Tunja, Colombia, from "Vecinos y moradores de Tunja" |

Flavio Álvarez Ángel cites a 1593 judicial record from Tunja, Colombia, in which a 23-year-old Cristóbal testified that his parents were Alonso de Rueda and Elvira González. Once in Tunja, Cristóbal de Rueda González married Damiana Pérez de Rosales (born c.1571; died c.1647 in Tunja). So far I have not been able to verify Álvarez Ángel's sources but amazingly Damiana's family can be traced back three more generations.

Tunja was "founded" by Spaniards in 1539, but the name was a mispronunciation of the town's original Muisca (Chibcha) Indian name, Hunza (also the name of a local chieftain). The Muisca tribe and closely related Guane tribe were conquered by the mid-1500s and their languages became extinct after the Spanish crown banned their being taught in 1770, but the heritage survived when some Indians inevitably had families with some of Cristóbal's descendants.

I write about the details of the lawsuit in my other blog, but it seems Cristóbal de Rueda was somehow implicated in his stepfather-in-law's alleged crimes. On August 13, 1601, court authorities stopped by Cristóbal's house, and his wife, Damiana Rosales, and her mother, María López, swore oaths and testified that Cristóbal was not in Tunja and they had no idea of his whereabouts. The authorities then proceeded to list the belongings in his house, in a presumed way to recover money for the prosecution.

2. Christóbal de Rueda

3. Alonso de Rueda

4. Juan de Rueda, who died before Damiana, as he is not mentioned in his mother's will, which says "several children" predeceased her.

5. Juana Rosales

7. María López

THE RUEDA SONS

The Church of Santa Bárbara in Tunja still has a copón (pyx, or a holder for the eucharist) made of gold-plated silver that was commissioned by Marcelo and bears the inscription: "Mando haser esta custodia Marcelo de Rueda, siendo año de 1632."

Marcelo married Isabel de Alvear, the daughter of Tunja master mason Rodrigo de Alvear, and had two children:

1. Isabel de Rueda Alvear

2. José de Rueda Alvear.

1. Juan de Rueda Sarmiento, a cleric who was possibly a Jesuit. His parish in 1672 was the Royal Mines of the Río del Oro, in Bucaramanga, and by 1705 his parish was at Curití. He had a daughter:

1a. María de Rueda, who married Luis Forero Uribe.

2. José de Rueda Sarmiento (born c.1635; died c.1702 in San Gil) was a landowner and gambler who sold small plots of his land to pay off his debts. He married Felisiana de Sotomayor (born 1641 in Bogotá), the great-great-great-great-granddaughter of the Inca emperor Túpac Inca Yupanqui. Their children included:

2a. José de Rueda Sotomayor (born 1671, baptized 1674 in Moncora, now Guane).

2b. Ana de Rueda Sotomayor (born and baptized 1675 in Moncora), who married Ignacio Díaz del Castillo (1670-1731).

2c. Catalina de Rueda Sotomayor (born 1676, baptized 1680 in Moncora).

2d. Cristóbal de Rueda Sotomayor (born 1679, baptized 1680 in Moncora), who married Juana López.

2e. María de Rueda Sotomayor (born 1684, baptized 1686 in Moncora; died c.1768 in Moncora), who married Diego Pérez Cancino (died 1732 in San Gil).

2f. Juan de Rueda Sotomayor (born 1687, baptized 1688 in Moncora).

3. Francisca de Rueda Sarmiento married Juan Rodríguez Durán (born 1631 in Garrovillas de Alconétar, Extremadura, Spain) and their children included:

3a. Cristóbal Rodríguez Durán y Rueda (born c.1654), who married his cousin María Díaz Sarmiento.

3b. Juan Rodríguez Durán y Rueda (baptized 1665 in Girón), who married his cousin Damiana Martínez de Ponte (1667-1725).

3c. José Rodríguez Durán y Rueda

3d. Antonio Atanasio Rodríguez Durán y Rueda

4. Ana de Rueda Sarmiento (baptized 1636 in Moncora)

5. Beatríz de Rueda Sarmiento (baptized 1638 in Moncora), who married Juan de Sarache y Chacón.

6. Cristóbal de Rueda Sarmiento (baptized 1638 in Moncora)

At some point between 1638 and 1645, the widowed Catalina married Captain Manuel Gómez Romano, a.k.a. Manuel Currea Betancur (born c.1616 in Portugal). They had at least seven children - the start of the famed Gómez Romano line.

Alonso de Rueda Rosales (born 1605? in Tunja; died April 1681 in Moncora), a landowner and exploitative slave owner who lived by the Río Suárez, first married Margarita Sarmiento de Olvera (died c.1659), the younger sister of Catalina, and they had at least nine children:

1. Marcela de Rueda Sarmiento (died before 1681), who married Luis Martínez de Ponte (born in Pravia, Asturias; died c.1696 in San Gil) around 1658 in Moncora and they had 9 children:

1a. Diego Martínez de Ponte (baptized 1659 in Moncora; died c.1710 in San Gil)

1b. Marcelo Martínez de Ponte

1c. Margarita Martínez de Ponte

1d. Catalina Martínez de Ponte (baptized 1665 in Moncora)

1e. María Martínez de Ponte (baptized 1666 in Moncora)

1f. Damiana Martínez de Ponte (born 1667; baptized 1669 in Moncora; died 1725 in San Gil)

1g. Alonso Martínez de Ponte (born 1670; baptized 1673 in Moncora)

1h. Fernando Martínez de Ponte

1i. Luis Martínez de Ponte (born 1674; baptized 1681 in Moncora)

2. Alonso de Rueda Sarmiento (baptized 1643 in Moncora; died before 1681) was a priest. His father's will read in part: "I declare that when Alonso de Rueda Sarmiento, my deceased son, was ordained as a priest, for his clerical salary and for him to get this dignity I marked 4,000 pesos of his inheritance from two residences in Butaregua and two slaves named Gracia and Julián." It's shocking to see that profits from the slave trade funded the salaries of the clergy! Genealogías de Santa Fé de Bogotá falsely claims that Alonso de Rueda Sarmiento died in 1720, confusing him with his nephew of the same name.

3. Cristóbal de Rueda Sarmiento (baptized 1645 in Moncora; died before 1681), who married his first cousin Francisca Sarmiento.

4. Pablo de Rueda Sarmiento (died c.1694 in San Gil), who married Feliciana Díaz y Cozar, daughter of his first cousin.

5. Bernardo de Rueda Sarmiento (born c.1646; died 1720 in San Gil), who married his first cousin Cecilia Sarmiento (born 1661, baptized 1664 in Moncora) and their children included:

5a. Alonso de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1678, baptized 1680 in Moncora; died 1721 in San Gil), who married Francisca Ortíz. There is more on his family in the following post.

5b. Miguel de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1681, baptized 1683 in Moncora)

5c. Juan de Rueda Sarmiento, who married Ana María Gómez Farelo y Pineda in 1704 in Guane.

5d. Josefa de Rueda Sarmiento, who married Juan Gómez Farelo y Pineda in 1704 in Guane.

5e. Cristóbal Javier de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1686, baptized 1687 in Moncora; died 1747 in Guane), who owned the land where Zapatoca was founded. He married Micaela Gómez Farelo y Pineda in 1720 in Guane, and there is more on his family in the following post.

5f. Marcelo de Rueda Sarmiento (baptized 1692 in San Gil; died 1758 in Guane), who married Gabriela Ortíz.

6. María de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1650; baptized 1652 in Moncora; died before 1681), who married Martín Sánchez de Cozar (born c.1644) and died childless.

7. Bárbara de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1657; baptized 1659 in Moncora; died before 1681), who married a Spaniard, Captain Juan de Amaya y Villarroel, a lieutenant at the royal mines of Bucaramanga and Betas, and had at least four children:

7a. Margarita Amaya Rueda (born 1671; baptized 1674 in Moncora), who married Antonio de la Parra Cano (c.1657-1729) and whose descendants include the Pradilla family.

7b. Tomás Amaya Rueda (born 1677, baptized 1679 in Moncora)

7c. Agustina Amaya de Sánchez

7d. Pedro Amaya Rueda

8. Nicolás de Rueda Sarmiento (born c.1657; died c.1715 in San Gil) first married his first cousin Gabriela Sarmiento y Cozar (d. c.1692) and had four children:

8a. Jacinta de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1682; baptized 1684 in Moncora)

8b. Bernardo de Rueda Sarmiento (baptized 1686 in Moncora)

8c. Salvadora de Rueda Sarmiento (baptized 1688 in Moncora), who married Pedro Gómez Romano Currea (c.1680-1739)

8d. Margarita de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1691, baptized 1693 in San Gil)

Nicolás then married in 1693 Rosa Florencia Ortíz Gómez, the daughter of another first cousin, and they had six children:

8e. Nicolás Ignacio de Rueda y Ortíz (born 1695 in San Gil), who applied but failed to enter the Universidad del Rosario [Rosary University] in Santa Fé de Bogotá in 1714.

8f. Clara Gabriela de Rueda y Ortíz

8g. Juana Gertrudis de Rueda y Ortíz

8h. Gabriel Evaristo de Rueda y Ortíz

8i. María de Rueda y Ortíz

8j. Francisco de Rueda y Ortíz

Nicolás married a third time to Catarina Gómez, and they had three children:

8k. Felipe Victor de Rueda y Gómez

8l. Francisca Plácida de Rueda y Gómez

8m. Bárbara Petronila de Rueda y Gómez

9. Felipe de Rueda Sarmiento, who is mentioned in Alonso's 1681 will.

10. Francisco de Rueda Sarmiento (born c.1657; died c.1703 in San Gil) married in 1686 in Moncora his first cousin, Justina Sarmiento y Cozar, and had four children:

10a. Josefa de Rueda Sarmiento (baptized 1689 in Moncora)

10b. Francisca de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1691, baptized 1692 in San Gil)

10c. Rosa de Rueda Sarmiento

10d. Juana María de Rueda Sarmiento

Francisco married a second time to María de Zuñiga, and had two more children:

10e. Juana de Rueda y Zuñiga

10f. Isabel de Rueda y Zuñiga

Alonso de Rueda Rosales also had an illegitimate daughter:

1. Catalina de Rueda, who married Salvador de Medina and whose daughter, Antonia de Medina, is mentioned in Alonso de Rueda Rosales's 1681 will.

Margarita Sarmiento also had an illegitimate daughter:

1. Fulana Sarmiento, who became the founding mother of the de la Prada family (including her great-grandson Melchor de la Prada, the founder of Zapatoca).

After Margarita Sarmiento died, Alonso de Rueda Rosales married Gerónima Ramírez de Poveda, daughter of Juan Ramírez de Benavides and Micaela de Poveda. Their children included:

1. Juan de Rueda Ramírez (born 1661; baptized 1664 in Moncora)

2. José de Rueda Ramírez (born 1666; baptized 1668 in Moncora)

3. María de Rueda Ramírez (baptized 1671 in Moncora)

ALONSO DE RUEDA AND HIS SLAVES

|

| Signature of Alonso de Rueda Rosales (1658) |

On April 9, 1681, an ailing, septuagenarian Alonso de Rueda Rosales completed and signed his will before witnesses in the settlement of Moncora. Within eight days Alonso was dead. The will and resulting probate case shows how Alonso steadily built his family's fortune on the frontier of Santander through acquiring land, raising livestock, and the buying and selling of Afro-Colombian people.

In his will, Alonso de Rueda Rosales wrote that he only owned about 12 or 14 mares when he married Margarita Sarmiento around 1640 in Moncora. Margarita's father, Captain Juan Sarmiento de Olvera, provided a substantial dowry of 2,020 pesos de a ocho reales in livestock, farms (estancias), and other goods. By the time Margarita died around 1656, Alonso estimated that he had 600 cattle, 60 mares and a jack donkey (in order to produce mules), 30 female donkeys (or jennies), 30 horses, and 200 goats and sheep. At the end of this list of animals, Alonso said he also owned 7 slaves, but only named six: Gracia, Susana, Andrés, Bartolomé, Julián, Miguel. The seventh was probably Juan, mentioned below.

There is a 1664 baptismal record for Miguel, the son of Gracia, both slaves of Alonso de Rueda. These are probably two of the same seven people that Alonso named as his property.

When Alonso de Rueda Rosales married a second time to Gerónima Ramírez de Poveda around 1659, he received a dowry of only 300 pesos a ocho reales from his wife's uncle, the Alférez José Ramírez de Benavides. Alonso also started to give dowries and endowments to his adult children, and slaves were a crucial part of these transactions.

It's important to note that in Alonso's will the slaves were always listed after the herds of cattle, goats, and sheep, but before the mules and horses. Also, the most expensive inanimate object owned by Alonso de Rueda Rosales was a fondo de cobre (probably a copper pot used in a trapiche, or sugar cane mill) worth 180 patacones and 2 reales, which was left to his oldest surviving son, Bernardo de Rueda Sarmiento. So a copper pot was valued by these slave owners as worth about half a human being.

Gracia (born 1631?) and Julián (born 1640?) were two slaves that Alonso de Rueda Sarmiento mortgaged to help launch his son Alonso's career as a priest. The younger Alonso also got "4,000 pesos of his patrimony" and two farms (estancias) in Butaregua from his father. When Margarita Sarmiento died, 25-year-old Gracia was valued at 400 patacones and 16-year-old Julián was valued at 380 patacones.

Susana (born 1631?) was described as de nación angola (of the Angola people). She was 25 years old when Margarita Sarmiento died, and was valued at 400 patacones. In 1671 Susana appeared in an inventory of Gerónima Ramírez's dowry. She is not mentioned in Alonso's 1681 will, and may have died by this time.

Andrés (born 1638?) was 18 years old when Margarita Sarmiento died, and was valued at 400 patacones.

An unnamed enslaved mulato man (Andrés?) was given by Alonso to his son, Cristóbal de Rueda Sarmiento, when he married Francisca Sarmiento. This unknown man was then sold by Cristóbal to Alférez Pedro Balduz for 350 patacones.

Isidro, an enslaved mulato man worth 340 patacones, was given by Alonso to his son, Pablo de Rueda Sarmiento.

Juan (born 1650?, called mulato) was 6 years old when Margarita Sarmiento died, and was valued at 150 patacones, or less than Alonso de Rueda's copper pot. When Juan was presumably grown and worth 400 pesos, he was given by Alonso to his son, Bernardo de Rueda Sarmiento.

Bartolomé (born 1650?, called negro), was 6 years old when Margarita Sarmiento died, and was valued at 150 patacones, or less than Alonso de Rueda's copper pot. When Bartolomé was presumably grown and worth 400 pesos, he was given by Alonso to his son, Francisco de Rueda Sarmiento.

Miguel (born 1652?, called mulato) was probably the son of Gracia baptized in 1664. He was 4 years old when Margarita Sarmiento died, and was valued at 120 patacones, or less than Alonso de Rueda's copper pot. When Miguel was presumably grown and worth 400 patacones, he was given by Alonso to his son, Nicolás de Rueda Sarmiento.

Gerbasia (born 1661?, called mulata), a 10-year-old enslaved girl worth 300 patacones, was given by Alonso to his daughter, Bárbara de Rueda Sarmiento, when she married Captain Juan de Amaya.

Two daughters of Susana (probably the one mentioned above), named Teodora (born c.1657) and Jacinta (born c.1661), were inherited by Gerónima Ramírez de Poveda from her late husband Alonso. Teodora was described in Alonso's probate case as nursing a baby girl (con una criada al pecho) named María.

An unnamed 80-year-old enslaved negra woman was not mentioned in Alonso's will but a subsequent probate inventory. Given her age, this woman could have possibly raised Alonso from childhood. The inventory coldly says that the woman was "not profitable or of any service," so that is why she was previously overlooked.

A few interesting details about Alonso de Rueda Rosales's life can be found amid the probate case's repetitive lists of livestock, slaves, lands, and inventories of household items. One is that Alonso served for 20 years as the mayordomo of the cofradía of the Santísimo Sacramento, one of several Catholic social groups in Moncora that probably led religious processions during Holy Week (Semana Santa).

In an absurd portion of the probate case, Luis Martínez de Ponte, who married Alonso's late daughter Marcela de Rueda Sarmiento, explained that he should inherit the portion of Alonso's livestock that descended from two cows and two mares that Marcela received 40 years before, as a newborn, from her maternal great-grandmother, Beatríz de Torres. Marcela's uncle and aunt, Manuel Gómez Romano and Catalina Sarmiento, testified that the cows and mares were intended for Marcela, but Marcela's brother Pablo argued that the animals were given to their mother, Margarita Sarmiento. Both sides then called witnesses to explain how they remembered that gifting of livestock from 40 years before.

THE FOUNDING SARMIENTO

Cristóbal and Alonso de Rueda Rosales married two daughters of a Spaniard, Captain Juan Sarmiento de Olvera (born c.1570 in Jérez de la Frontera, Andalucía, Spain), and his wife, Francisca González de la Nava, who was a mestiza (mixed Spanish and Indian ancestry).

Surviving documents show Juan signed his name as simply "Juan Sarmiento." In the 1670s, Flórez de Ocáriz misspelled Juan's name as "Juan Sarmiento de Olivera," and to this day more historians and genealogists use the incorrect spelling. The name "Sarmiento de Olvera" may refer to the town of Olvera, Cádiz, Spain, which is more than 50 miles from Juan's hometown of Jérez de la Frontera. Flórez de Ocáriz says Juan's parents were Alonso de Olivera Sarmiento and Mariana de Guerra y Valderrama, and that the Olivera family was from Germany, the Guerra family came from Asturias de Santillana, and the Valderrama family came from Frías, Burgos, Spain. "Sarmiento" appears on the Inquisition's Jewish surname list.

Juan Sarmiento was a young man when he came to the New World around 1590, and settled in Vélez, Colombia, a town founded in 1539 in the heart of Guane Indian territory. Around 1600 Juan married Francisca González, and in 1609 he got permission to have Indians work on his hacienda in the area north of the town of Vélez. A colonial official who visited Juan Sarmiento's lands in 1638 made a snide but fascinating remark that Juan's house had a "much greater amount of male and female Indians and riff-raff [indios e indias y chusma]." The social and genetic mestizaje that Spanish officials sneered at is in the DNA of all of us descended from Juan Sarmiento.

Francisca González de la Nava's great-grandfather was a conquistador, Bartolomé Hernández Herreño (1502-1559), who came from Spain to the New World at the age of 28. Bartolomé first entered Colombia as part of the final expedition of Ambrosio Alfinger [Ambrosius Ehinger], which ended with Alfinger's death in 1533. Bartolomé then returned to Colombia at age 37 as part of the armada of Nikolaus Federmann. There, Bartolomé discovered the Río de Oro (River of Gold) in the Santander region. He fought much of the region's indigenous population, and he and his grown son died during an Indian rebellion, when they were hit by poisoned arrows and died in agony soon afterwards (for more details, read Los compañeros de Féderman by José Ignacio Avellaneda Navas).

A grandson of Bartolomé, Francisco Sánchez Herreño, was a cleric who disregarded his vows and had a relationship with Beatríz de Torres, a mestiza from Turmequé, an ancient Muisca (Chibcha) settlement. As described above, Beatríz lived to see the birth of her great-granddaughter, Marcela de Rueda, in the 1640s.

Again, we only know that Beatríz de Torres was mestiza, and there's no proof that her Indigneous mother was related to Diego de Torres's Indigenous mother, or the cacique of Turmequé. Online family trees linking Beatríz de Torres to the cacique of Turmequé have no supporting evidence.

1. María Antonia Sarmiento de Olivera married Juan Díaz Bermúdez, a landowner in Vélez, and had at least seven children:

1a. Juan Díaz Sarmiento.

1b. Martín Díaz Sarmiento (baptized 1633 in Moncora)

1c. Francisco Díaz Sarmiento, who married Gertrudis del Castillo and whose children were the "Díaz del Castillo" family.

1d. Alonso Díaz Sarmiento, who never married.

1e. María Díaz Sarmiento (baptized 1637 in Moncora)

1f. Catalina Díaz Sarmiento (baptized 1640 in Moncora)

1g. Gracia Díaz Sarmiento (baptized 1643 in Moncora; died 1733 in Girón), who married Pedro de Uribe Salazar. She was an exploitative slave owner who in 1699 sold a 6-year-old boy named Ignacio, the son of Victoria, a woman she enslaved. In 1732, this elderly slaver gave two of her slaves, a 6-year-old girl named Laureana and a 10-year-old boy named Alejandro, to her grandchildren.

2. Catalina Sarmiento de Olivera, who by 1635 had married Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales (born c.1596), and then by 1645 had married the Portuguese-born Captain Manuel Gómez Romano (born c.1616). The six children of Catalina and Cristóbal are listed above, and the children of Catalina and Manuel were (order unknown):

2a. Catalina Gómez Romano y Sarmiento (baptized 1646 in Moncora, now Guane)

2b. María Gómez Romano y Sarmiento (baptized 1650 in Moncora)

2c. Manuel Gómez Romano y Sarmiento (born c.1650; died 1732 in San Gil).

2d. Juana Francisca Gómez Romano y Sarmiento

2e. Alonso Gómez Romano y Sarmiento

2f. Ignacio Gómez Romano y Sarmiento

2g. Leonardo Currea Betancur (born c.1655), the attorney who led the legal procedures that founded the city of San Gil (1689) and secured its coat of arms (1694).

3. Juana Sarmiento de Olivera married Lázaro de Quiñónes Rincón and their children included:

3a. Antonio de Quiñones (baptized 1637 in Moncora)

3b. Salvador de Quiñones

3c. Fray Lázaro de Quiñones (baptized 1646 in Girón)

3d. Juana de Quiñones

4. Margarita Sarmiento de Olivera (died c.1660 in Moncora), who married Alonso de Rueda Rosales (1605?-1681) and bore his children and also had an illegitimate daughter, seen above.

5. Leonor Sarmiento de Olivera, who married a Spaniard named Francisco Mantilla de los Ríos y Palacios (1608-1679), founder of the city of Girón, Santander, Colombia in 1630, had at least six children:

5a. Diego Mantilla de los Ríos

5b. Toribia Mantilla de los Ríos

5c. Francisca Mantilla de los Ríos

5d. Leonor Mantilla, wife of Francisco de la Roza

5e. Lope Mantilla de los Ríos (baptized 1652 in Girón)

5f. Gutierre Mantilla de los Ríos (baptized 1655 in Girón)

6. Alonso Sarmiento de Olivera married Cecilia González de Cozar. The genealogist Juan Flórez de Ocáriz said Alonso and Cecilia had four boys and three girls, but it seems they had more children, including:

6a. Juan Sarmiento, who was a priest by 1681.

6b. Cecilia Sarmiento de Rueda (born 1661; baptized 1664 in Moncora)

6c. Alonso Sarmiento y Cozar (born c.1664; died 1754 in Barichara)

6d. Tomás Sarmiento y Cozar (born 1669; baptized 1670 in Moncora; died c.1745 in San Gil)

6e. Gabriela Sarmiento de Rueda (died c.1692)

6f. Justina Sarmiento de Rueda (born 1671; baptized 1677 in Moncora)

6g. (probably) Francisca Sarmiento de Rueda

7. Fray Francisco Sarmiento de Olivera, a priest.

THE FOUNDING OF SAN GIL

As early as 1620, a subdivision of the town of Vélez was informally known as "Santa Cruz." The 1681 probate case of Alonso de Rueda Rosales lists people as "residents of Vélez in the province of Guane," but they had other names for specific sites of settlement such as "San Francisco" and "San Martín." In the late 1600s, the white and mestizo settlers in "the province of Guane" began acquiring charters to give Spanish names to the original Indian settlements and bring in more colonial government.

In 1688 the attorney Leonardo Currea Betancur led a group of landowners living near the Guane settlements of Mochuelo and Guarigua to submit a petition to found a town. They came up with the name "Santa Cruz y San Gil de la Nueva Baeza," to flatter the Spanish viceroy, Don Gil de Cabrera y Dávalos. The viceroy officially approved the naming of a new settlement on March 17, 1689. The flattery paid off again when King Carlos II "the Bewitched" of Spain approved an edict on October 27, 1694 that gave San Gil the title of "Villa" (Town) and a coat of arms, seen at the top of this post. That in turn gave the town the regional government and tax collection through the 1700s (for more details, read Presencia de un pueblo by my grandfather Rito Rueda Rueda, Historia de San Gil en sus 300 años by Isaías Ardila Díaz, and Liberalism and Conflict in Socorro, Colombia by Richard Stoller).

The original 1688 petition lists 51 male residents and nearly half were linked by blood or marriage.

The following 7 were members of the Rueda family: Joseph de Rueda Sarmiento (an alcalde ordinario, or town magistrate, son of Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales), Juan de Rueda Rosales, Nicolás de Rueda Rosales, Christóbal de Rueda Sarmiento, Bernando de Rueda Sarmiento, Pablo de Rueda Rosales, and Francisco de Rueda Sarmiento (sons of Alonso de Rueda Rosales).

Another 13 were cousins of the Rueda Sarmiento families: Alonso Sarmiento de Olbera, Thomas Sarmiento de Olbera, Manuel Gómez Romano, Martín Díaz Bermudez, Lorenzo Díaz Bermudez, Francisco Díaz, Marcelo Díaz, Alonso Díaz, Joseph Díaz Sarmiento, Ignacio Díaz del Castillo, Juan Durán, Cristóbal Durán, and Leonardo Currea Betancur.

Four more had married into or were in-laws of the Rueda or Sarmiento families: Gabriel Angel Ortíz Navarro, Antonio de la Parra Cano, Juan Rodríguez Durán, Martín Sánchez de Cozar.

It's very important to note that many of these men were the descendants of colonizers who made their living as the owners of encomiendas, a Latin American equivalent of plantations, which had entire Indian villages work for a single Spanish or criollo (creole) landowner. In 1561, a number of encomenderos in Vélez, including several of my ancestors, were accused of forcing the local Indians to relocate, toil in mines and fields, and even work as beasts of burden. A court document charged that there was only "a tenth" of the number of local Indians from ten years before, and that colonizers turned a blind eye as Indians died of disease and mistreatment. Subsequent generations also brought in African slaves to do hard work, and through rape or marriage the blood of the slave owners and the enslaved intertwined. An excellent case study of 17th- and 18th-century slaves and slave owners in the town of Girón is "Esclavos y libertos en la jurisdicción de Girón, 1682-1750" by Yoer Javier Castaño Pareja. The encomienda system declined from the 1700s onwards, as Indian communities died out or were disbanded, landowners sold smaller plots to control their debts and the numerous heirs fought titanic, embittered legal battles over inheritance (for details, read Stoller mentioned above, or El solitario: El conde de Cuchicute y el fin de la sociedad señorial by Juan Camilo Rodríguez Gómez).

ORIGINS OF OTHER SANTANDER FAMILIES

These histories mostly involve Spaniards coming to Santander, but there are also a few Santander surnames of indigenous origin. The historian Mario Acevedo Díaz wrote that a 1760 census of Zapatoca includes five surnames of Guane Indian origin: Cabarique, Chivatá, Ine, Taguada, and Useche.

My investigation would not be possible without the two-volume Las genealogías del Nuevo Reino de Granada by the 17th-century genealogist Juan Flórez de Ocáriz, as well as FamilySearch.org posting Santander's parish records and notarial records online. I also gained great insights from genealogist Rodolfo Useche Melo and the essay "Apellidos regionales de Colombia" by genealogist Flavio Álvarez Ángel. The multi-volume Genealogías de Santa Fé de Bogotá is helpful but contains many errors that are copied in the family trees of Geni.com and Ancestry.com.

Acevedo (Acebedo) - The Acevedo family descends from Captain Pedro Gómez de Orozco (born c.1517 in Fuenteovejuna, Andalucía [or Bizkaia?], Spain; died after 1583 [1601?] in Pamplona, Norte de Santander, Colombia). Pedro Gómez de Orozco arrived in Colombia in 1536 and then joined the expedition of Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada. Some say the Acevedo surname comes from Pedro Gómez de Orozco's son Gonzalo marrying a daughter of the conquistador Andrés de Acevedo. Others say the surname comes from Pedro Gómez de Orozco's grandson Francisco marrying Elvira de Peñalosa Acevedo y Rangel (born c.1578 in Pamplona), a daughter of Bernardino Fernández de Peñalosa, a conquistador from La Mancha, Spain. I side with the latter theory since the family frequently used the "de Peñalosa Acevedo" surname through the 1600s and 1700s, before shortening the surname to "Acevedo." I would appreciate learning about more primary sources that could clarify this family's origins.

Amaya - My ancestor Juan de Amaya Villaroel (born in Arcos de la Frontera, Andalucía, Spain; died c.1689 in San Gil, Colombia) was the son of Pedro de Amaya and Agustina de Villaroel. Juan served as a royal lieutenant at the mines of Bucaramanga and married Bárbara de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1657; died before 1681).

Ardila - My ancestor Captain Pedro de Ardila came from Castilla la Vieja, Spain and arrived at Vélez in 1540 with the expedition of Governor Lebrón. Pedro married Francisca Gutiérrez de Aponte, the daughter of another veteran of Lebron's expedition. Another ancestor of mine, Gonzalo de Ardila, who is probably descended from Pedro de Ardila, married Madalena Mejía in the early 1600s, and their sons settled in San Gil.

Arenas - Unknown origin. My ancestor Felipe de Arenas, who lived in Colombia in the early 1600s, married María de los Ángeles y Porras, a possible descendant of María de los Ángeles, a daughter of the 16th-century conquistador Juan de Castro. A son of Felipe de Arenas and María de los Ángeles, Bernardo de Arenas (died 1704 in San Gil, Colombia), settled in Santander and married first María de Zabala, then Micaela Ponce de Mendoza. A grandson of Bernardo de Arenas, Melchor de la Prada y Arenas Mendoza (c.1711-1789), founded Zapatoca.

Benítez - My ancestor Lorenzo Benítez (born c.1520) was born in Almendralejo, Extremadura, Spain to a family originally from Cabeza del Buey, Extremadura. He came to Colombia around 1550, married Inés Ortíz Galeano, and was among the residents of Vélez accused of mistreating Indians in 1561. Another ancestor with the same surname, Juan Francisco Benítez, married Úrsula de Quiñones (c.1659-1744?) in Girón, and their son José Benítez (born 1679 in Girón) married Juana Rodríguez Durán y Martínez (born c.1689 in Guane).

Berbeo - My ancestor Francisca Berbeo, who married Salvador de Rueda y Gómez Farelo (c.1729-1796) and settled in Zapatoca, was the daughter of Andrés Justino Berbeo and the granddaughter of Domingo Antonio Berbeo (born in Oviedo, Asturias, Spain; died 1714 in Socorro), who served as Socorro's chief justice of the Inquisition. Juan Francisco Berbeo (1729-1795), first cousin of Francisca, was a Socorro resident who led the Comuneros' revolt in 1781.

Díaz - My ancestor Juan Díaz Bermúdez was born in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Andalucía, Spain and settled in Vélez, Colombia by 1609. He married María Sarmiento de Olvera, daughter of the Spaniard Juan Sarmiento de Olvera. Juan Díaz's parents, Juan Bermúdez Canario and Inés de Salazar, were born in the Canary Islands. Juan Díaz's maternal grandfather, the conquistador Gonzalo Hernández Gironda, owned an encomienda named Queca near Bogotá, Colombia in the mid-1500s.

Durán - My ancestor Juan Rodríguez Durán (born c.1631 in Garrovillas de Alconétar, Extremadura, Spain), a founder of San Gil, married Francisca de Rueda Sarmiento, the daughter of Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales and the granddaughter of the Spaniard Cristóbal de Rueda.

Ferreira - Unknown origin. My ancestor María Ferreira (died 1783 in Barichara) was first married to Diego Martínez de Aponte in the 1710s and then married Juan Francisco Díaz del Castillo in the 1720s in San Gil. María is possibly descended from Juan Ferreira, the first husband of Catalina Gómez Romano y Sarmiento (born c.1646 in Guane).

Galvis (Gálvez) - Unknown origin. My ancestor Teresa Galvis married Joaquín Rueda and they had children in the 1790s in Barichara. The first Galvis in San Gil records is Laureano de Galvis, who baptized his daughter Salvadora in 1693.

García - Unknown origin. My ancestor Teresa García de Sierra lived in Girón and married José de la Prada in the late 1600s. The García de Sierra family frequently appears in Girón's notarial records. Another ancestor with the same last name, Petronila García (died 1758 in Zapatoca), married Bernardo de Rueda Ortíz (c.1703-1771) in the 1720s in Guane.

Gómez Farelo - My ancestor Manuel Gómez Farelo was born in Portugal, came to Colombia, and married Lucía González de Azcárraga, who was born in Vélez. Their birthplaces are mentioned in the will of their son, Pablo Gómez Farelo y González (c.1635-1705). Pablo married Juana de Pineda (1660s-1725) in 1677 in Guane. Lucía González de Azcárraga's paternal grandfather, Juan de Azcárraga y Erostegui (c.1555-1603) came from Oñati, Gipuzkoa, Spain.

Gómez Romano - My ancestor Captain Manuel Gómez Romano, also known as Manuel Currea Betancur, was born c.1616 in Portugal. He married Catalina Sarmiento de Olvera, the widow of Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales, around 1640 in Vélez, Colombia. Some of the descendants of Manuel and Catalina used the last name "Gómez Romano," while others used the surnames "Gómez Currea," "Gómez Currea Betancourt," or "Currea Betancur."

González del Busto - My ancestor Toribio González del Busto was born in Asturias, settled in Colombia, married Catarina Díaz Sarmiento (baptized 1640 in Vélez), and lived in Girón by the 1660s.

León - My ancestor Pedro de León Carreño (died 1771 in Zapatoca) was probably related to the León Carreño family of Ocaña, Norte de Santander, Colombia. In the 1720s Pedro married María Páez (died 1779 in Zapatoca), who may have been a relative of Andrés Páez de Sotomayor, who founded the city of Bucaramanga in 1622.

Linares - Unknown origin. My ancestor José Linares married Hipólita Serrano Solano y González (baptized 1683 in Girón; died 1754? in Guane) around 1700 in Girón.

Macías (Masías) - Unknown origin. My ancestor Tomás Masías (died c.1781) married María Rosalía Díaz in 1754 in Barichara. Early Macías settlers in Santander include Matías Macías, who lived in Girón in the 1680s, and Francisco Masías, who lived in Guane around 1700. Francisco's possible sons Manuel Masías (born c.1701) and Bernardino Masías (born c.1708) lived in Zapatoca.

Martínez de Ponte (Martínez de Aponte) - My ancestor Luis Martínez de Ponte (born c.1636 in Pravia, Asturias, Spain; died c.1696 in San Gil, Colombia) was the son of Diego Martínez de Ponte and Catalina Inclán de Estrada. After settling in Moncora (now Guane), he married Marcela de Rueda Sarmiento (died before 1681) around 1658 and they had nine children. The misspelling "Martínez de Aponte" first appeared in records in the 1700s.

Meneses - Unknown origin. My ancestors were two sisters named Micaela de Meneses and Jerónima Meneses. Micaela de Meneses married Gonzalo de Pineda in 1660 in Chanchón (now Socorro), and happens to be my grandfather Rueda's direct maternal ancestor. Jerónima Meneses married José Martín Moreno in 1673 in Chanchón. The historian Horacio Rodríguez Plata says Micaela and Jerónima were the daughters of the Alférez Pedro Tello de Meneses, but I have not been able to verify that.

Orejarena - Unknown origin. My ancestor Miguel de Orejarena (born in Spain; died 1766 in Zapatoca) had a Basque last name meaning "the property/estate of Oreja," and Oreja is Spanish for ear. Miguel married Lucía de Rueda Sarmiento (born 1691) in 1717 in Guane, and they had a son, Miguel de Orejarena y Rueda (born c.1718).

Ortíz Navarro - My ancestor, Captain Gabriel Ángel Ortíz Navarro (born c.1649 in Sevilla, Andulcía, Spain; died 1723 in San Gil, Colombia), settled in San Gil and served as alcalde ordinario in 1708. He first married Juana Gómez Romano and then married Violante de Uribe Salazar. Genealogías de Santa Fé de Bogotá lists a different birth year for Gabriel, but my estimate is based on the ages he gave in Guane notarial records.

Parra - My ancestor Juan de la Parra Cano (born c.1625 in Azuaga, Extremadura, Spain; died c.1699 in San Gil, Colombia) was a founder of San Gil and owned an encomienda in Charalá. He married Francisca Benítez Galeano (born c.1627 in Vélez, Colombia). Juan's grandparents, Pedro de la Parra and Catalina Vázquez, lived in Arévalo, Ávila, Castilla-León, Spain, and Juan's father, Antonio de la Parra, moved to Azuaga and married Isabel García Cano in 1604.

Pérez - Unknown origin. My ancestor Domingo Pérez married Andrea de Arenas (born c.1688 in Girón) in the early 1700s in Girón. Domingo and Andrea's son, Romualdo Pérez (died 1773), married Bárbara Gómez Serrano (c.1726-1783) in 1745 in Girón and then settled in Zapatoca.

Pineda - Unknown origin. My ancestor Gonzalo de Pineda married Micaela de Meneses in 1660 in Chanchón (now Socorro), and their daughter Juana de Pineda (1660s-1725) married Pablo Gómez Farelo (1635-1705) in 1677 in Guane.

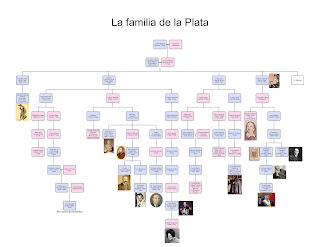

Plata - My ancestor Francisco Félix de la Plata y Domínguez (born c.1661 in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Andalucía, Spain; died 1730 in Socorro, Colombia) came to Cartagena, Colombia in 1682, settled in Chanchón (now Socorro) in 1685 and became a military captain. Francisco Félix married Josefa Martín Moreno (born 1675 in Chanchón; died c.1765 in San Gil) in 1688 in Socorro. The genealogist Rocío Sánchez did an excellent investigation of the de la Plata family, verifying historian Horacio Rodríguez Plata's account that Francisco Félix's father, José Antonio Márquez de la Plata of Sevilla, Spain, had added "de la Plata" to his surname. The Márquez family can be traced back another five generations, and the family came to Sevilla from Castropol, Asturias. The earliest-known patrilineal ancestor of Francisco Félix, his 4th-great-grandfather Vibian Pérez Márquez, had come from Lobeiro, Galicia near the Spanish-Galician border. The Márquez family is said to have originated in Luaces, Galicia.

Prada - Unknown origin. My ancestor José de la Prada married Teresa García de Sierra in Girón by the 1680s. I know nothing about José de la Prada's father, but three informaciones matrimoniales from the 1700s involving José's descendants in San Gil say José's mother was named "Francisca de la Peña Montoya" or "Fulana Sarmiento." Francisca / Fulana was perhaps born around 1640, and was the "natural" daughter of Margarita Sarmiento de Olvera (died c.1656). I don't know if Francisca / Fulana was born out of wedlock, from an annulled marriage, or other circumstances. Therefore, José de la Prada is the great-grandson of the Spaniard Juan Sarmiento de Olvera, and the grandfather of Melchor de la Prada (c.1711-1789), the founder of Zapatoca.

Quijano - Unknown origin. My ancestor Casimiro Quijano (died 1802 in Zapatoca) may be descended from the Bustamante Quijano family of Vélez, but I have found no supporting evidence. Casimiro married María Luisa Plata Gómez (born c.1749 in Zapatoca; died 1794 in Zapatoca) in 1764 in Zapatoca.

Serrano - My ancestors Juan Serrano Solano and Francisca Jaimes Calderón (died 1696) married in 1632 in Pamplona, Colombia and lived in the tiny town of Guaca, Santander, Colombia. It is unclear whether Juan was related to the Serrano Cortés family of Pamplona, Vélez, and Socorro. Francisca Jaimes Calderón was probably a granddaughter of two Spaniards, the conquistador Cristóbal Jaimes and Juan Calderón de la Barca. In turn, Juan Calderón de la Barca descended from the noble Calderón de la Barca family of Barreda, Cantabria, Spain, and the great poet Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600-1681) is a distant relation. The children of Juan Serrano Solano and Francisca Jaimes Calderón include Juan Serrano Solano, who wrote a will in 1688 in Pamplona, and Diego Serrano Solano, who married Catalina González del Busto y Díaz and is the forefather of most Serrano families of Santander.

Tello de Mayorga - My ancestor Manuela Tello de Mayorga, a resident of San Gil, married Martín Gómez Romano in the 1720s. She is possibly descended from the father-and-son conquistadors Francisco de Mayorga and Juan de Mayorga, who lived in Andalucía and whose ancestors came from León, Spain. They sailed from El Puerto de Santa María, Spain to Puerto Rico in 1534. Juan de Mayorga married María de Cazalla y Tello in Santo Domingo, accompanied the Adelantado Alonso de Lugo to Colombia in 1543, and settled in Vélez.

Uribe - My ancestor Captain Pedro de Uribe Salazar (born in Bilbao, Bizkaia, Spain) probably came to Colombia in the 1620s and married Ana de Sanabria Pavón in 1630 in Vélez. Pedro's parents, Francisco de Uribe and Marina de Gorostizaga, married in 1607 in Bilbao, and Pedro's maternal grandparents, Pedro de Gorostizaga and María de Zárate, married in 1582 in Bilbao. The more famous Uribe family of Antioquia, Colombia, including former President Álvaro Uribe Vélez, descends from a different Basque ancestor, Martín de Uribe Echaverría (born 1656).

Vargas - My ancestor Josefa Vargas y Rueda (born 1763 in San Gil?; died 1790 in Barichara) married Miguel Gómez Wandurraga. It's possible that Josefa is the paternal granddaughter of the Spaniard Francisco de Vargas y Hinestrosa (born 1698) and the sangileña Cecilia Sarmiento y Gómez de Orozco. In turn, Francisco de Vargas y Hinestrosa supposedly belonged to the "Vargas Machuca" family founded by the 13th-century warrior Diego Pérez de Vargas.

Vesga - My ancestor Juan de Vesga Santiago (born in Spain, died c.1684 in Girón, Colombia) married Antonia de Uribe Salazar (died c.1695 in San Gil) in 1651 in Chanchón (now Socorro). Antonia was the daughter of the Spaniard Pedro de Uribe Salazar.

Wandurraga - Unknown origin. My ancestor Miguel Ignacio de Aguiluz y Wandurraga lived in San Gil in the early 1700s. He also signed his name as "Miguel de Wandurraga" and "Miguel de Ubandurraga." His Basque surnames were originally spelled "Egiluz" and "Urandurraga" or "Undurraga." He married Catarina de la Parra Jaimes, granddaughter of the Spaniard Juan de la Parra Cano.

Zárate - My ancestor María Ortíz de Zárate (1670s? - fl.1736), a resident of San Gil, married three times, first to a man named Cortés, then to Diego Martínez de Aponte y Rueda (c.1657-c.1710), and then to Juan de León Santana. María was possibly descended from Domingo Ortíz de Zárate (born 1593 in Burgos, Spain), who came to Colombia in 1629 as part of the retinue of the 2nd Marquis of Sofraga, the newly-appointed governor of Nueva Granada. Domingo married the widow Constanza de Velasco Salazar in 1631 in Vélez. Domingo's paternal line claimed descent from the House of Zárate de Aguirre, based in Vitoriano or Marquina in the province of Álava, Spain, which in turn claimed descent from the Lords of Ayala, supposed descendants of the kings of Pamplona.

THE NUMEROUS, ILLUSTRIOUS DESCENDANTS

|

| The Rueda Building in the center of San Gil, which faces the main plaza. |

An incomplete chronological list, gleaned from the multi-volume Genealogias de Santa Fé de Bogotá, El tribuno de 1810, and various online genealogies, includes:

~ Many of the officers and soldiers in the Comunero rebellion of 1781, which was a massive, armed demonstration in several Colombian provinces against by unfair taxation by colonial officials, a full generation before the more radical war for independence from Spain. John Leddy Phelan's "The People and the King" is probably the best book in English on this unique, momentous political movement.

~ Pedro Fermín de Vargas Sarmiento (1762-1813), a lawyer, scientist, and economist who conspired for Colombia’s independence alongside Francisco de Miranda and Antonio Nariño, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano. Here's an El Tiempo article on Vargas.

~ Emigdio Benítez Plata (died 1816), who taught many Colombian founding fathers and who signed Colombia’s Declaration of Independence in 1810, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano, Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz, and Juana Sarmiento de Quiñones.

~ The priest Francisco Javier Serrano Gómez de la Parra Celi de Alvear (died 1817), who also signed Colombia’s Declaration of Independence and was nicknamed "Dr. Panela" for his sweet temperament, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano.

~ José Acevedo y Gómez (1772-1817), a lawyer and brilliant orator nicknamed “The Tribune of the People” who publicly proclaimed the Colombian Declaration of Independence in Bogotá on July 20, 1810, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano, and Alonso Sarmiento de Olvera. Interestingly, his snobbish great-grandson was intent on finding royal descent, and claimed (mistakenly or intentionally) in a biography that José Acevedo was from the "de la Parra Celi" family of Tunja, whose forefather, the conquistador Jorge Celi de Alvear, was directly descended from the Spanish Dukes of Medinaceli and Kings Alfonso X of Castilla y León and Louis IX of France. Historians like José Ignacio Avellaneda Navas have since determined that Jorge Celi de Alvear was a fictional man. José Acevedo's Parra ancestor, Juan de la Parra Cano, came to Colombia a couple of generations after the "de la Parra Celi" family.

~ President Fernando Serrano y Uribe (1779-1818), who wrote the Pamplona Province's constitution in 1815 and served in 1816 as the last president of the Patria Boba, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and her two husbands Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales and Manuel Gómez Romano, and Juana Sarmiento de Quiñones.

~ Antonia Santos Plata (1782-1819), who led a guerrilla army with her brother Fernando, supported Simón Bolívar's army, and was imprisoned and executed by the Spanish, was descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz. Antonia's nephew, the politician and journalist Francisco Santos Galvis (1848-1900), became the forefather of the Santos political dynasty, which includes two presidents.

~ Vicente Azuero Plata (1787-1844), a founder of Colombia’s Liberal Party and associate of Francisco de Paula Santander, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales, and Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz.

~ The historian and poet Josefa Acevedo y Tejada (1803-1861) and her magistrate husband Diego Fernando Gómez Durán (1786-1853) were cousins who were descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano, and Alonso Sarmiento.

~ Rito Antonio Martínez Gómez (1823-1889), a leading Conservative politician who served on the Colombian Supreme Court, was descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz.

~ President Aquileo Parra Gómez (1825-1900), a leading Liberal politician who lead Colombia from 1876-1878, as the country emerged from civil war and expanded its railroads, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano.

~ The economist Salvador Camacho Roldán (1827-1900), who was also a leading Liberal politician and governor of Panama, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano.

~ Carlos Martínez Silva (1847-1903), a Conservative minister, journalist, and Colombian ambassador to the United States right before the first U.S. invasion of Panama, was descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz.

~ President Clímaco Calderón Reyes (1852-1913), who served for one day in 1882 after the incumbent president died, and who also served as ambassador to the United States, was descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz.

~ The famous poet José Asunción Silva (1865-1896), one of the founders of Latin America’s Modernist movement, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano.

~ José María de Rueda y Gómez (1871-1945), an eccentric hacienda owner and coffee exporter who referred to himself as the “Count of Cuchicute,” was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano, Alonso Sarmiento de Olvera, and Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz. To learn more, read this article by historian Germán Arciniegas and this article by Juan Camilo Rodríguez Gómez, author of El Solitario: El Conde de Cuchicute y el fin de la sociedad señorial (1871-1945).

~ The writer Tomás Rueda Vargas (1879-1943) was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano, and Alonso Sarmiento.

~ Dr. Maximiliano Rueda Galvis (1886-1944), Colombia’s first psychiatrist, was descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz.

~ Ofelia Uribe Durán de Acosta (1900-1988), a Colombian feminist and advocate for women’s suffrage, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales, and Margarita Sarmiento and Alonso de Rueda Rosales.

~ Santiago Martínez Delgado (1906-1954), a leading 20th-century Colombian artist and muralist, was descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz.

~ President Virgilio Barco Vargas (1921-1997), who served from 1986-1990 during the height of Colombia’s drug violence, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales, and Margarita Sarmiento and Alonso de Rueda Rosales.

~ Alvaro Mutis Jaramillo (1923-2013), one of Colombia’s greatest writers and poets, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales, and Margarita Sarmiento and Alonso de Rueda Rosales.

~ Julio Mario Santo Domingo Pumarejo (1924-2011), a billionaire beverage mogul who was once one of the world’s richest men, was descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz. His granddaughter, Tatiana Santo Domingo (born 1983), married Andrea Casiraghi (born 1984), the eldest grandson of Prince Rainier III of Monaco and Grace Kelly, and their children are Sasha (born 2013), India (born 2015), and Maximilian Rainier Casiraghi (born 2018).

~ Luis Carlos Galán Sarmiento (1943-1989), the populist politician who was assassinated by Pablo Escobar’s henchmen while running as a Liberal presidential candidate, was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Cristóbal de Rueda Rosales, and Margarita Sarmiento and Alonso de Rueda Rosales.

~ Carlos Pizarro Leongómez (1951-1990), another assassinated presidential candidate, was the commander of the M-19 guerrilla movement who helped plot the infamous 1985 siege of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá. This odious man was descended from Catalina Sarmiento and Manuel Gómez Romano and Alonso Sarmiento, and his direct ancestors included José Acevedo y Gómez and Josefa Acevedo y Tejada.

~ President Juan Manuel Santos Calderón (born 1951), who served as the president of Colombia from August 7, 2010 to August 7, 2018 and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on October 7, 2016, is descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz.

~ Vice President Francisco “Pacho” Santos Calderón (born 1961), who served from 2002-2010 under former President Alvaro Uribe and is President Juan Manuel Santos's double first cousin, is also descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz.

~ Vice President Germán Vargas Lleras (born 1962), who served from 2014-2017 under former President Juan Manuel Santos, is descended from Antonia Sarmiento de Díaz.

As the internet says, "big if true." This would make Adrián de Gorraiz a "gateway ancestor," the Navarrese immigrant who links his run-of-the-mill Colombian family to the broader family tree of European royalty. Tibaut's brother, Luis II de Beaumont, married Leonor de Aragón, the half-sister of King Fernando II of Aragón, who along with cousin-wife Queen Isabel I of Castilla y León ruled as the first "Catholic Kings" of Spain! The same couple who finished the reconquista of Spain, funded the genocidal rapist Christopher Columbus, and mercilessly expelled all Jews from their kingdom, all in the same momentous year of 1492! Tibaut's sister (or niece?), Anna de Beaumont, was the lady-in-waiting of Queen Juana la Loca, daughter and heir of the Catholic Kings, and as "Grand Mistress of the Imperial Household" raised Juana's children, including three future queens and Emperor Carlos V. Having a close connection to this much heinous history is dizzying.

- Kings of France, as recent as King Jean II "the Good" (reigned 1350-1364, and a direct ancestor of Empress Josephine, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte).

- Iberian kings including King Jaime I "the Conqueror" of Aragón, Kings Alfonso VI and Alfonso VIII of Castilla, and King Sancho Garcés III "the Great" of Pamplona.

- Military leaders such as El Cid, Simon de Monfort the 5th Earl of Leicester, and Eustace II the Count of Boulogne (and possible patron of the Bayeux Tapestry).

- St. Vladimir "the Great," the Grand Prince of Kiev.

- English monarchs like King Henry II and King Henry III of England, Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, King William "the Conqueror" and his Norman ancestor Rollo the Viking, King Harold II who was killed by William the Conqueror's army, and King Alfred "the Great" of Wessex.

- Hungary's Árpád dynasty, which claimed descent from Attila the Hun.

- Byzantine Emperors Alexios I Komnenos, John II Komnenos, Isaac II Angelos, and Alexios III Angelos. The last two ruled during the Fourth Crusade, leading up to the Sack of Constantinople (1204).

- Holy Roman Emperors Charlemagne, Otto I, and Frederick Barbarossa.

17. King Philippe III of France (1245-1285), reigned 1270-1285

Some argue that the Robertian kings were not descended from Charlemagne, but the marriage of King Philip II of France (#14 in the above tree) and Isabelle of Hainault in 1180 was seen as a union of the Robertian and Carolingian dynasties. So here's the alternative path from Charlemagne to King Louis VIII of France:

~ Funny enough, while tracing descent from Charlemagne is still seen as a mark of prestige, contemporary statisticians and geneticists say having Charlemagne as an ancestor is not that unique. They theorize that everyone with European ancestry is probably descended from Charlemagne, as well as from every other European who lived during Charlemagne's time and left descendants. This principle of pedigree collapse shows that any two people on Earth are 50th cousins or closer relations. (Here's more on humanity's common ancestors.)

~ According to Flórez de Ocáriz, Domingo's great-great-grandfather, Sancho de Zárate de Apodaca, was a son of the "ancient and noble House of Zárate de Aguirre," located in the village of Vitoriano or Marquina, in the province of Álava, Spain. Both villages are near another village called Zárate.

~ The Zárate family claims descent from Rodrigo Ortíz de Zárate (fl. 1200), the illegitimate son of the 6th Lord of Ayala. Rodrigo's great-great-grandfather, the 3rd Lord of Ayala, married the daughter of the Lord of Salcedo, who claimed descent from the kings of Asturias, stretching back to Ramiro I (reigned 842-850) who according to legend first saw Santiago Matamoros (St. James the Moor-Killer) in battle, his father Bermudo I (reigned 789-791), and his great-grandfather, Duke Pedro de Cantabria (died 730, Rodrigo's 15th-great-grandfather), who helped his fellow nobleman Don Pelayo keep the Moors from conquering Asturias. The chroniclers claimed that Duke Pedro came from the Visigothic royal line of King Leovigildo (reigned 568-586) and his son King Recaredo I (reigned 586-601). Recaredo I took the major step of converting from Arianism to Roman Catholicism, leading the rest of the Visigoth ruling class to convert and cementing the Catholic Church's hold on Spain for the next 1,400 years.

~ Rodrigo Ortíz de Zárate's 4th-great-grandfather, Don Vela Sánchez, was the 1st Lord of Ayala and the supposed bastard son or grandson of King Ramiro I (c.1007-1063), the first king of Aragón. Ramiro I in turn was the illegitimate son of King Sancho Garcés III "the Great" of Pamplona (c.990-1035), who conquered and briefly ruled over most of Christian Iberia, from the border of Galicia to Barcelona, before he was assassinated. Sancho III arranged to divide his kingdom among his sons: García Sánchez III got Pamplona, Fernando I got León, and as noted before, Ramiro I got Aragón. These kingdoms were finally reunited in 1469, when a 12th-great-grandson of Ramiro I, King Fernando II of Aragón, married a 17th-great-granddaughter of Fernando I, Queen Isabel I of Castilla y León. Remember them from further up the page?

~ Sancho III's kingly line stretches back to his 6th-great-grandfather, the first king of Pamplona, Eneko Aritza (Íñigo Arista, c.790-852), who helped free his region from Frankish rule nearly a half-century after the bloody year 778, when Charlemagne burned Pamplona to the ground and the Basques had decisive revenge at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass. Another interesting ancestor, Sancho III's 3rd-great-grandmother Onneca Fortúnez (c.850-after 890), began life as a princess in Pamplona but was obliged to settle in Córdoba after the Moors defeated her father in battle and took him captive. Onneca, now called the Arabic name "Durr" (Pearl), married Abdullah ibn Muhammad, the son of the emir of Córdoba, and may have even converted to Islam. After two decades in Andalucía, Onneca abandoned her Muslim children, returned to Pamplona and resumed her old identity, and married her royal first cousin. A grandson from Onneca's second marriage (the ancestor of Sancho III) became the king of Pamplona, while a grandson from Onneca's first marriage, Abd-ar-Rahman III (889-961), proclaimed himself the Caliph of Córdoba and built the renowned Medina Azahara. Under the rule of Abd-ar-Rahman and his trusted advisor, the Jewish doctor Hasdai ibn Shaprut (c.915-970), Córdoba was Europe's largest, most cosmopolitan, and enlightened city. Its distinguishing character was the convivencia of Muslims, Jews, and Christians, which historian David Levering Lewis defined as "tolerance secured by restrictions" (details here).

~ Flórez de Ocáriz wrote that Constanza de Velasco Salazar claimed descent on her father's side from the House of Ungo de Velasco, founded by Diego Sánchez de Velasco in the early 1300s, and the House of San Pelayo, founded by one of the 120 illegitimate children of the feudal lord Lope García de Salazar (c.1264-1344).

~ Diego Sánchez de Velasco was the son of two prominent courtiers in Castilla-León, Sancho Sánchez de Velasco (died 1315) and Sancha García de Carrillo. Sancho served as adelantado mayor under King Fernando IV and Sancha was the aya y camarera mayor (governess and head chambermaid) of King Fernando's daughter Leonor (1307-1359), who became the queen of Aragón. Sancho de Velasco died while fighting the Moors in Gibraltar, following the footsteps of his Velasco forefathers who took part in the Reconquista. His great-grandfather died in the Battle of Alarcos (1195, a major Moorish victory), his grandfather took part in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212, a major Moorish defeat), and his father helped reclaim Sevilla from the Moors (1247-1248). Sancho Sánchez de Velasco was descended on his mother's side from the House of Castro, founded by his 4th-great-grandfather Fernando García de Hita (c.1065-1135), who had married a 6th-great-granddaughter of the Catalan count Guifre the Hairy (d. 898), who founded the House of Barcelona. Sancha de Carrillo was descended from the House of Osorio, founded by her 4th-great-grandfather Osorio Martínez (c.1107-1160), whose ancestors supposedly include an Asturian princess and even a knight who fought in the mythical Battle of Clavijo.

~ Sancho Sánchez de Velasco and Sancha de Carrillo both descended from the previously mentioned King Sancho III of Pamplona and his grandson King Alfonso VI of Castilla y León (c.1040-1109), who is remembered for the reconquest of Muslim-controlled Toledo in 1085. I am amused that one of Alfonso VI's more notable defeats is called the "Treason of Rueda" (1083), referring to when the Moorish governor of Zaragoza promised to surrender to Alfonso VI at the castle at Rueda de Jalón, but instead ambushed the Castilian troops and killed many noblemen. The warrior El Cid then hastened to Rueda de Jalón to broker an end to the fighting. On his mother's side, Alfonso VI was descended from kings of León, and Duke Pedro de Cantabria was his 10th-great-grandfather. Alfonso VI married five times, and his second wife, Constance of Burgundy, had a daughter who became Queen Urraca of Castilla y León (c.1080-1126), the 4th-great-grandmother of Sancho Sánchez de Velasco. Alfonso VI and the noblewoman Jimena Muñoz had an illegitimate daughter, Elvira Alfónsez (c.1079-c.1157), who became the mother-in-law of Osorio Martínez and the 5th-great-grandmother of Sancha de Carillo.

~ Queen Urraca, the daughter and heir of Alfonso VI, first married Count Raymond of Burgundy, a scion of the powerful House of Ivrea and brother of Pope Callixtus II (reigned 1119-1124). While Pope Callixtus II is remembered for the Concordat of Worms, I am more interested in his papal bull "Sicut Judaeis" (1120), which tried to stop the slaughter and forced conversion of Jews. Raymond and his papal brother had a Norman grandmother, making them the first cousins once removed of King William the Conquerer of England and the 4th-great-grandsons of Rollo the Viking (c.846-c.930), first ruler of Normandy.

Queen Urraca of Castilla y León, my supposed 27th-great-grandmother and ancestor of the House of Ungo de Velasco and the Gorraiz family. (Source)

~ After Alfonso VII's death, his two sons divided the kingdom, and then in 1158 Alfonso's 2-year-old grandson inherited the throne of Castilla. The House of Castro (backed by the king of León) and the House of Lara started a civil war over who would be the young king's regent. At the Battle of Lobregal (1160), Osorio Martínez, fighting for the House of Lara, was killed by his own son-in-law, Fernando Rodríguez de Castro. While the House of Castro did not regain the regency, Fernando Rodríguez de Castro gained enough prestige in the Leonese court to dissolve his first marriage and wed his first cousin Estefanía la Desdichada, who was also the king of León's half-sister. This marriage came to a horrifying end in 1180, when Estefanía was stabbed to death by her jealous husband. Since the king of León left the murder of Estefanía unpunished, some historians have assumed that Estefanía had an affair, but the exact circumstances remain obscure. Estefanía's son, Pedro Rodríguez de Castro, became the mayordomo of the kings of León and the great-grandfather of Sancho Sánchez de Velasco.

~ Diego Sánchez de Velasco's son, Juan Sánchez de Velasco "the Gallant," built his family castle, the Torre de Ungo, in Valle de Mena, Burgos, Spain. The Velasco and Salazar families then entered a nasty blood feud during the Castilian Civil War (1351-1369), when the Salazar family backed King Pedro I and the Velasco family backed his half-brother, Enrique de Trastámara. Enrique's mother was the widow of Juan Sánchez de Velasco's first cousin, also named Juan Sánchez de Velasco. After Enrique de Trastámara killed his half-brother and became king, the Velascos tore down 27 casas fuertes (fortresses) that belonged to the Salazars. In Valle de Mena the Velasco-Salazar blood feud raged on, long past the civil war, until a final truce came in 1433 (details are in Las Merindades de Burgos by María del Carmen Arribas Magro).

~ Under the Trastámara and Habsburg dynasties, the descendants of Diego Sánchez de Velasco's brother Fernando became Grandees of Spanish royalty. Fernando's great-great-grandson, Pedro Fernández de Velasco (1425-1492) became a "condestable of Castilla," and the title stayed among his male descendants until 1713. Pedro's sons Bernardo and Íñigo, who participated in the final reconquest of Moorish land in Spain, later became the first two Dukes of Frías. A 3rd-great-grandson of Íñigo Fernández de Velasco became King João IV of Portugal when the country broke away from Spanish control in 1640.

~ The House of Ungo de Velasco lasted until 1576, when the 6th-great-granddaughter of Juan Sánchez de Velasco "the Gallant" married into the House of La Revilla. The Torre de Ungo gradually fell into ruin, and according to historian José Bustamante Bricio the remaining walls of the castle were sold in 1887 and broken up to make ballast for the tracks of the La Robla Railroad, which still runs from León to Vizcaya.

~ On her mother's side, Constanza de Velasco Salazar was a great-great-granddaughter of Juan Martín Hincapié, a conquistador from the expedition of Nikolaus Federmann (1536-1539) and encomendero of Moniquirá, near Vélez.

~ Fray Felipe de la Gándara's "Descripción, armas, origen, y descendencia de la muy noble y antigua casa de Calderón de la Barca" (here are the 1661 edition and the expanded 1753 edition) preserves the stories of at least 17 generations of the Calderón de la Barca family, beginning with the founder Fortún Ortíz Calderón, son of the 6th Lord of Ayala. The family legend says that Fortún did not cry at birth, and needed to be dipped into a cauldron (caldera) in order to be revived. You can imagine the father proudly saying "I needed a big cauldron (calderón) for my boy!" and that becoming the child's last name. The family coat of arms shows five cauldrons topped with banners (pendón y caldera), but Gándara explains that in heraldry this represents the financial ability to raise and provide for an army to serve the king. Fortún became a "settler" of Baeza, Andalucía, Spain in 1227 after it was taken back from the Moors, took part in King Fernando III's campaign to conquer Sevilla (1248-1253), and served as the alcalde of Toledo.

~ Fortún's son, Sancho Ortíz Calderón (died c.1279?), founded the Casa de Villanueva de la Barca in Viveda, Cantabria, Spain. His casa-torre, which was later expanded into a palace, still stands today. Since the family operated a ferry (barca) by their casa-torre, they acquired the last name "Calderón de la Barca." Sancho was a commander in the military Order of Santiago under King Alfonso X, and his descendants proudly noted that he was "martyred" by the Moors after fighting them near Gibraltar, probably during the Spaniards' first Siege of Algeciras (1278-1279). The story goes that the Moors captured Sancho, brought him to Morocco, saw how valient he was, and offered him freedom if he converted to Islam. Sancho chose to remain Christian and was executed. The Calderón coat of arms has the legend "Por la fe moriré" (I will die for the faith), in honor of Sancho's martyrdom. The family also used the patronymic surname "Sánchez Calderón" for centuries in memory of their forefather in shining armor.

1. King Eneko Aritza [Íñigo Arista], first king of Pamplona, reigned c.824-852. His half-brother was the Moorish leader Musa ibn Musa al-Qasawi.

2. King García Iñíguez of Pamplona, reigned 852-882.

3. King Fortún Garcés of Pamplona, reigned 882-905.

4. Onneca Fortúnez, the princess of Pamplona discussed above who was held captive in the Córdoba emirate, whose second husband was her royal cousin Aznar Sánchez.

5. Toda Aznárez, who married King Sancho Garcés I of Navarra, reigned 905-925.

6. King García Sánchez I of Navarra, reigned 925-970, who married a daughter of the Count of Aragón.

7. King Sancho Garcés II of Navarra, reigned 970-994, who married the daughter of the Count of Castilla.

8. King García Sánchez II of Navarra, reigned 994-1000, who married the daughter of the Count of Cea.

9. King Sancho Garcés III "the Great" of Navarra, reigned 1000-1035, who with his mistress Sancha de Aibar had:

10. King Ramiro I of Aragón, reigned 1035-1063. His illegitimate son or grandson was:

11. Vela Sánchez de Aragón, 1st Señor de Ayala, who married a daughter of the Lord of Vizcaya.

12. Vela Velázquez, 2nd Señor de Ayala, who married a daughter of the Lord of Valle de Mena.

13. Galindo Velázquez, 3rd Señor de Ayala, whose wife came from the House of Salcedo.

14. Garcigalíndez de Salcedo, 4th Señor de Ayala, whose wife came from the House of Orozco, descendants of the Lords of Vizcaya.

15. Sancho García de Salcedo, 5th Señor de Ayala, who married a daughter of the Count of Piedrolas.

16. Fortún Sanz de Salcedo, 6th Señor de Ayala and camarero of King Alfonso X, who with his mistress María de Espina had:

17. Fortún Ortíz Calderón (born c.1190), Señor de Nograro, who married Hurtada de Mendoza, a daughter of the Casa de Mendoza. I will discuss the (largely fictional) genealogy of the House of Mendoza in the next section. Fortún's sister Berenguela López de Salcedo became the 3rd-great-grandmother of Leonor de Guzmán, mistress of King Alfonso XI of Castilla-León and foremother of the House of Trastámara. Another sister of Fortún, Elvira Ortíz Calderón, married the warrior Lope García de Salazar and became the foremother of the House of Salazar, seen above.

18. Sancho Ortíz Calderón (died c.1279), Señor de la Casa de Villanueva de la Barca, who married Maria de Zamudio and died a prisoner of war.

19. Pedro Sánchez Calderón, Señor de la Casa de la Barca, who married Blanca de Mendoza, daughter of Rodrigo de Mendoza. I assume that Rodrigo was related to Hurtada de Mendoza mentioned above, but it's unclear how.

20. Hernán Sánchez Calderón, Señor de la Casa de la Barca, who married María Fernández de la Vega. María belonged to the Casa de la Vega, founded by Diego Gómez de la Vega in the late 1100s.

21. Hernán Sánchez Calderón, Señor de la Casa de la Barca, who married Ana Gutiérrez de Monseñor.

22. Hernán Sánchez Calderón, Señor de la Casa de la Barca, who married Elvira Gutiérrez de Ceballos. Gándara claimed that Elvira was the 11th-great-granddaughter of King Fernando I of León (reigned 1035-1063), son of King Sancho III of Navarra. Elvira's great-aunt, Elvira Álvarez de Ceballos, married Fernán Pérez de Ayala (c.1305-1385), and their children included the poet and historian Pedro López de Ayala (1332-1407) and Inés de Ayala, a great-great-great-grandmother of King Fernando II of Aragón, husband of Queen Isabel I of Castilla y León.

23. Hernán Sánchez Calderón, Señor de la Casa de la Barca, married María de Velasco. María's maternal Ramírez de Arellano family claimed descent from the daughter of El Cid Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (c.1048-1099). Keep in mind that this claim seems to have no reliable documentation.

24. Rui Sánchez Calderón, Señor de la Casa de la Barca (probably named "Rui" after El Cid), married Sancha Gutiérrez de la Guerra. Through their daughter Mencia they became the possible 17th-great-grandparents of Simón Bolívar, the Liberator of South America. Rui may be mentioned in a document filed by his possible grandsons in 1412.

25. Hernán Sánchez Calderón "el Viejo," who married María de Teran y de los Rios.

26. Hernán Sánchez Calderón & Sancha Fernandez de Ceballos y Escalante [Note: this generation is only mentioned the expanded 1753 Calderón genealogy, not the original 1661 genealogy.]

27. Hernán Sánchez Calderón (fl. 1467), Señor de la Casa de la Barca, who married Juliana Ruiz Velarde (fl. 1493). This is the earliest generation that the chronicler Ángel de los Ríos y Ríos could identify in records.

28. Alonso Sánchez Calderón, who founded the Casa de Calderón in Sotillo, Palencia, Castilla, close to the border with Cantabria, married Maria de Obeso. His older brother Hernán inherited the Casa de la Barca, and his direct male descendants kept the title through the late 1700s. A distant descendant of Hernán still holds the title of Conde de Villanueva de la Barca today.

29. Pedro Calderón de la Barca, who married Isabel de Losa.

30. Pedro Calderón de la Barca (died c.1573), who married Elvira de Herrera. Pedro and his second wife Constanza Pérez were the great-grandparents of the writer Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600-1681).

31. Juan Calderón de la Barca, who settled in Pamplona, Colombia and married María del Basto.

32. Elvira Calderón de la Barca, who married Juan Jaimes in 1590 in Pamplona, Colombia.

33. Francisca Jaimes Calderón, who married Juan Serrano Solano in 1632 in Pamplona, Colombia.

34. Diego Serrano Solano, who married Catalina Gonzalez del Busto y Díaz. Their son José, daughter Salvadora, and daughter Úrsula are among my 7th-great-grandparents, and their daughter Hipólita is my 8th-great-grandmother.

~ Fray Felipe de la Gándara writes that the first Calderón, Fortún Ortíz Calderón, and his grandson married women from the Casa de Mendoza, a minor noble family from Álava province that only gained prominence in the 1300s. By Gándara's time, the House of Mendoza had concocted an ancient family tree that the Foundation for Medieval Genealogy calls "shaky," given a lack of supporting primary documents.

~ This fantastical family tree of Hurtada de Mendoza, wife of Fortún Ortíz Calderón, stretches back to her 13th-great-grandfather, El Infante Don Jaun Zuria, the mythological 1st Lord of Vizcaya. The son of a Scottish princess impregnated by either a Basque nobleman or the Basque serpent god Sugaar, Jaun Zuria is a literal "white knight" (as his name roughly means in Euskera) who battles the Asturians and Leonese in legends to assert Basque independence sometime in the 9th century AD.

~ Many lordly generations later, Jaun Zuria's supposed 9th-great-grandson Diego López de Mendoza, Señor de la Casa de Mendoza, married Leonor Hurtado, Señora de Mendibil. Leonor's father, Fernan Pérez Hurtado (c.1114-1156), was the illegitimate son of Queen Urraca of Castilla y León (c.1080-1126) and her lover, Pedro González de Lara (died 1130). Gándara identifies Fernan's father as Conde Don Gómez González, another lover of Queen Urraca.

~ The early Mendoza family tree is so convoluted that the presumed great-great-grandchildren of Diego López de Mendoza and Leonor Hurtado include Hurtada de Mendoza, the wife of Fortún Ortíz Calderón who lived in the 1200s, and Pedro González de Mendoza (1340-1385), who lived over a century later. Pedro helped the family fortunes by backing the House of Trastámara in the Castilian Civil War, bringing the House of Mendoza to prominence in the Spanish court for two centuries.

~ Through Queen Urraca, the House of Mendoza claimed descent from the Jiménez dynasty of Pamplona and the Capetian dynasty of France. The Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne is supposedly the 15th-great-grandfather of Hurtada de Mendoza, wife of Fortún Ortíz Calderón. Modern genealogists say there is no documentation proving that Queen Urraca's love child is the forefather of the House of Mendoza.

Alternative genealogies of the Calderón de la Barca family

~ I conclude this section on "noble ancestry" with the most famous lines written by my probable relation Pedro Calderón de la Barca, from a monologue in his 1635 play "La vida es sueño." These lines cut through the vanities of Spain's Golden Age that were fueled by conquest, fanaticism, and the spoils of slavery:

¿Qué es la vida? Un frenesí.

¿Qué es la vida? Una ilusión,

una sombra, una ficción,

y el mayor bien es pequeño:

que toda la vida es sueño,

y los sueños, sueños son.

por favor colocarle al blog en una esquina un cuadro que al darle click convierta el texto al español.

ReplyDeletehttps://encolombia.com/medicina/revistas-medicas/academedicina/va-15/profesor-maximiliano/

ReplyDeleteWas my Grandfather

Great work. I'm tired of the 'we all descend from noble conquistadores' so popular in Latin American genealogies. I want to know all about my ancestors fighting over cattle, gambling and intermarrying between cousins over the course of generations.

ReplyDeleteA la orden! 😉 Yes, the trope of "noble conquistadors" is tired, racist, and inaccurate. The truth is much more interesting. You'll love what I found about the first Colombian Rueda: he had to flee town to escape authorities! https://geneticfunhouse.blogspot.com/2024/05/cristobal-de-rueda.html

Delete